Emery Marc Petchauer

The Girl with All the Gifts

I’m excited to teach The Girl with All the Gifts by M. R. Carey this week in my Critical Literacies and Communities class. This is a science fiction/horror/dystopian novel that takes place 20 years after The Breakdown of society due to a fungus that turns humans into zombies, or, somewhat euphemistically, “hungries” as they are called throughout the novel. (Spoilers below.) Why have I placed this novel in a class about critical literacies and communities, and why read it with a class full of aspiring educators?

The answers to these questions started forming in 2015 when I read the novel shortly after its publication.

The central relationship in the novel is between a teacher and student: Miss Justineau and Melanie. It’s usually a hard pass for me on books that center student-teacher relationships. They are often so far removed from the actual work of education and what teaching in schools looks like today. And so is this one. But in a different way. Melanie is a hungry. The back cover introduces her like this:

Every morning, Melanie waits in her cell to be collected for class. When they come for her, Sergeant Parks keeps his gun pointed at her while two of his people strap her into the wheelchair. She thinks they don’t like her. She jokes that she won’t bite. But they don’t laugh.

Melanie is a hungry and Miss Justineau is a teacher in her “classroom” on a military base. The workers on the base have orders to study high functioning hungry children, like Melanie, for possible cures to the fungus. Studying them means collecting data on their cognitive and emotional responses to a simulated classroom setting. At least up until the lead scientist calls for a child hungry to dissect in her lab. Melanie is sweet, endearing, engaged, and all but passes for a normal child if it were not for the hunger to bite – yes, eat! – any human she might smell. Yet unlike the adult hungries in the outside world that have taken over, she has some capacity to recognize this urge, resist it, and remove herself from a situation where she might do the thing she would most regret: eat Miss Justineau. Of course, much of the action teeters on this edge, especially because Miss Justineau understands that Melanie is, indeed, the girl with all the gifts, and seeks to save her from the lead scientist’s plans.

That curriculum is so central to this world is one aspect that has me so interested to teach it. The curriculum given to the child hungries is from the pre-Breakdown world: fairy tales, Greek myths, and facts and figures about cities that have since fallen. Melanie’s cell is decorated with a picture of the Amazon rainforest and a kitten drinking from a saucer of milk. It’s an understatement to say that all of their textbooks are outdated. The curriculum around the child hungries is of a world that no longer exists. And they have no idea.

This context in the early part of the novel raises this question: how is curriculum equally outdated in classrooms today? What are we asking students to learn – to believe – that is of a world that no longer exists for them? I like these questions. I think about them a lot. And I want my classes to consider them too.

This question is brought to the fore when, as characteristic of the dystopian genre, the world constructed in the early part of the novel breaks down. In this case, the walls around the military base are breached and hungries swarm. Melanie, Miss Justineau, and three other characters with conflicting interests are thrust together into the beyond. For the first time, Melanie sees, smells, touches, and perceives the world as it is - in its horror and beauty - beyond the curriculum that constructed her reality in the classroom simulation. There are no kittens drinking from saucers of milk. There is no Amazon rainforest. The population of Birmingham is zero. Yet fragments of the classroom simulation curriculum continue showing up as she reconstructs her entire understanding of the world and what she is in it. How could they not? It’s all she has known.

The novel begins in a classroom, and it ends in a classroom. The penultimate classroom, however, is not a simulation like in the beginning. It’s Miss Justineau, Melanie, and a small group of hungry children - more feral than high-functioning like Melanie, but there is hope - gathered around a makeshift white board. They’ve accepted the new world that has begun, remade by a peculiar fungus, never to go back. They are students, and their teacher starts the lesson by writing the first letter of the alphabet on the board.

I struggle with the final scene. It’s teacher-centered. It’s direct instruction. It’s banking. The children (as we’ve come to accept them over the novel, no longer just hungries) are blank slates and empty receptacles. Paulo Freire would not be pleased. But herein lies the second question, and the second reason, I wanted to teach this novel: What should the education of these children look like on the cusp of this new world that is emerging before them?

This question is one introduced much earlier in the semester while studying visionary philosophy and organizing through the writings, recordings, and conversations of James and Grace Lee Boggs. The Boggses and comrades were thinking in context with post-1967 and post-industrialized Detroit. Central to their dialectical thinking is evolution of the human: a more human human – the phrase that shows up in their writing and is often used as a shorthand reference to the ontological commitments underwriting their theory of change. The Girl with All the Gifts ends at this point of emergence. The new world has begun. The (hungry) children will be the adults of this new world in which Miss Justineau and any other surviving adults cannot inhabit. What should education and learning look like?

I’m glad to be reading this novel as the class launches into the final third of the semester where we explore participatory approaches to learning. Participatory approaches and epistemologies have their own answers to this question. And the final scene of the novel invites us to answer the “what should” question through various educational approaches.

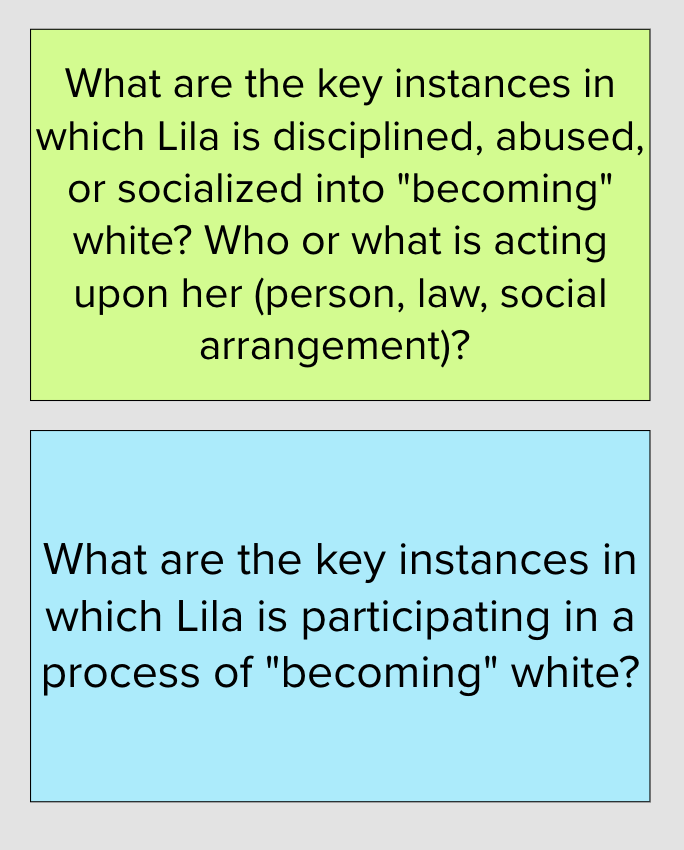

Discussion prompts this week from YA Lit + Antiracist Teaching, and our reading of Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White – informed by Morrison, Baldwin, Thandeka, and others.

Okay, one more thing about YA Lit + Antiracist Teaching this semester: I’m co-teaching part of the course with a veteran ELA teacher in SF who was (wait for it…) a participant in my diss over 15 years ago! She was “Malaya” in my first book. She went on to become an ELA teacher and I’ve learned so much from her over the years. I cherish her friendship. She is redesigning her unit on The Marrow Thieves, so we are going to bring my class into the authentic challenges posed by this redesign and pitch solutions that she might take up next year. I’ve often thought about how teacher education might have “teachers in residence” like humanities programs often have artists in residence (very different from a cooperating or mentor teacher), but the timing and labor demands on teachers never allow it. But she is on sabbatical this year, so she can engage with our class in a deep and sustained way. And I’m surely compensating her for time and expertise.

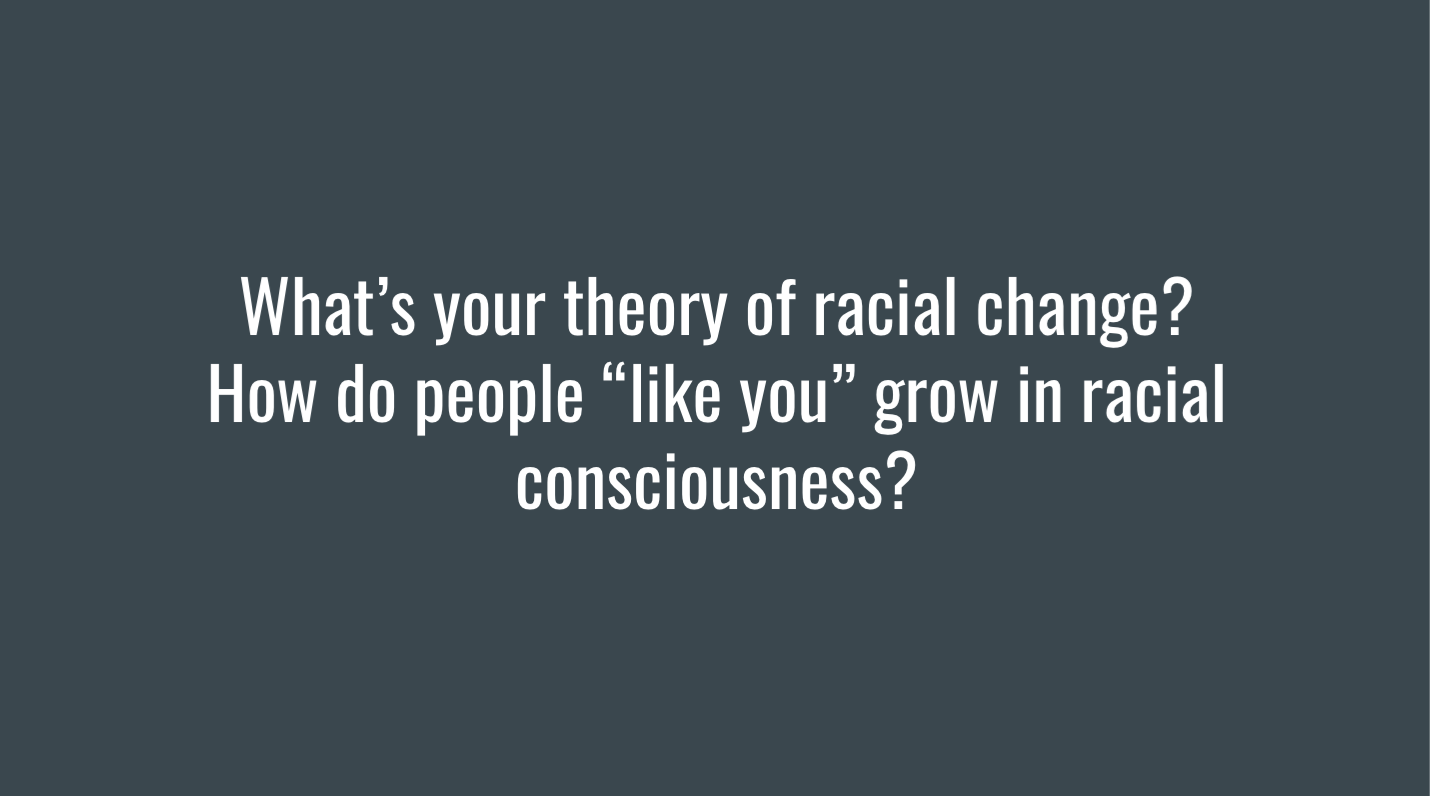

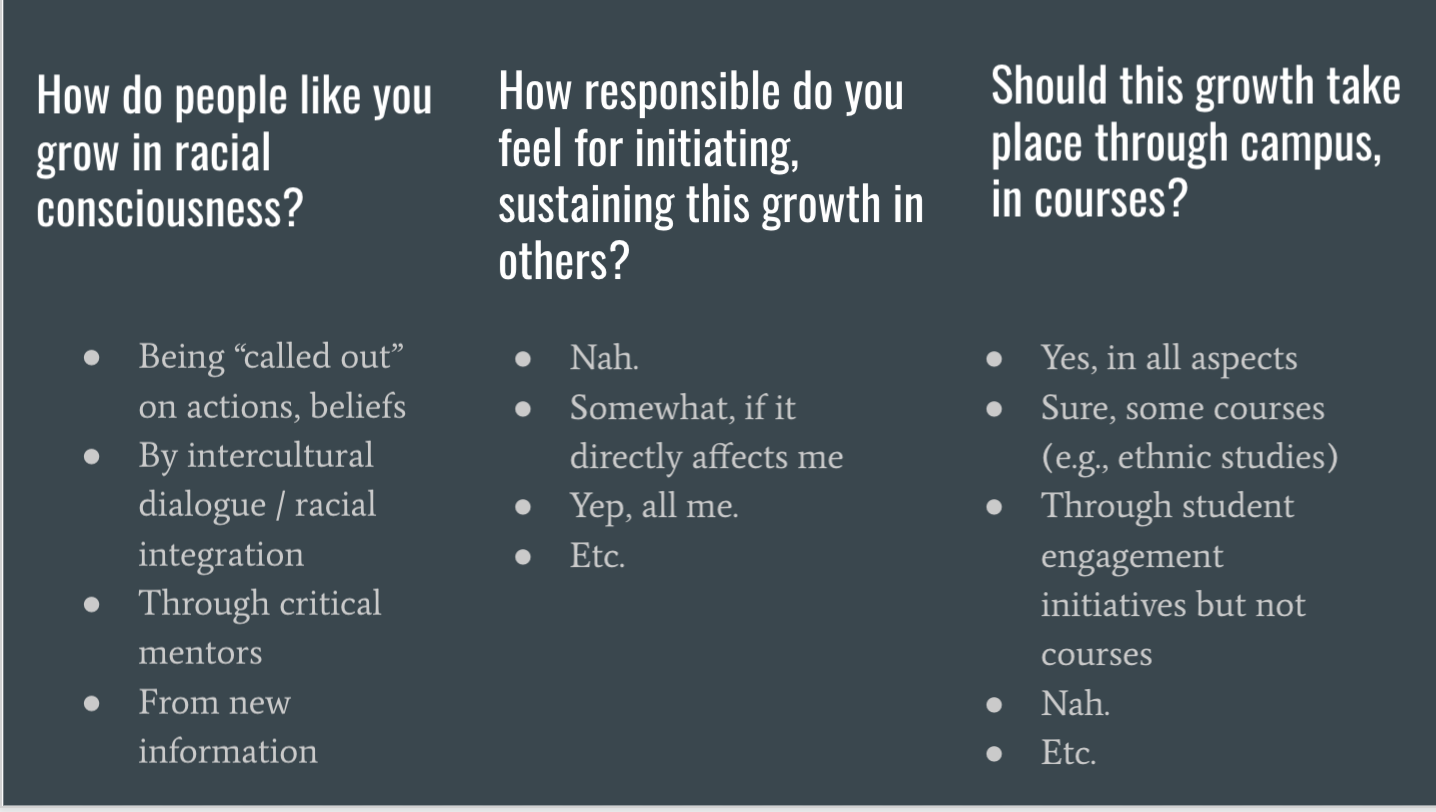

Theories of Change in Racial Consciousness: A Thought Exercise

This is a thought exercise I developed through the Race, Pedagogy, & Lit workshop series at Michigan State University.* The exercise tries to create dialogue and understanding among colleagues who might hold similar commitments to antiracism but take very different steps toward antiracist outcomes in courses and around campus. In a charitable environment, such colleagues are eager to understand one another. In an uncharitable environment, such colleagues may be suspicious of one another. The exercise is geared toward either environment.

Ground zero is this question:

This question draws from Eve Tuck’s article “Suspending Damage,” which discusses theories of change in social science research. The social science context isn’t important. Rather, it’s important people think about the tacit theories of change they have adopted regarding how people like themselves grow in racial consciousness.

The framing of this question toward people “like you” is useful. First, it allows people to take up the question in a range of ways. Second, it allows facilitators to prompt in certain directions, like asking white folks to think about how other white folks grow in racial consciousness.

We then link this question with two others relevant to the campus context. These three questions and the possible answers make up the thought matrix of the exercise. How you answer these questions reveals key components about the overall theory of change that guides your actions.

We then think about the kinds of actions that would follow from different configurations of answers. You can see one configuration in the series of green answers below. This person would likely be very vocal, all the time, and everywhere. Do you know anyone like this? Is this you? This person would also likely design courses and campus programing for explicit antiracist outcomes. The point here isn’t to evaluate this theory of change but to understand the actions that would follow from this particular configuration of answers.

But then if you were to change just one answer, the ensuing actions would also change. In this case below, the red answer would shape the curricular and campus programming decision faculty and staff make. This person would not wrap all courses and programming around antiracist outcomes, even though the answers in the first two columns have not changed.

And there are other options too. In the configuration below, this person feels less responsible for initiating growth in others. This might mean they are less vocal about issues that do not directly impact them.

And so on. Once again, the point in this exercise is not to evaluate theories of change. Some of them might be right. Some of them might be wrong. And there are always contradictions among theories of change because they operate across many scales and temporalities (another point from Tuck). Similarly, the point is not to reach consensus about which set of answers is right (though that may be an important step in a different process). The point is to understand how different answers to key question will result in different actions. Colleagues may be very similar to one another with respect to how they answer these questions, but the actions that result may be very different. Or colleagues may be very different from one another with respect to how they answer these questions, and that is why their actions are different.

I imagine there are many ways to remix this exercise. Different sets of questions and answers could populate this matrix and shift the purpose of the activity. The phrase “racial consciousness” early on could be substituted with something else as well.

*Thanks to my collaborators Briona S. Jones and Sen Kim for co-facilitating this Race, Pedagogy, and Lit series.

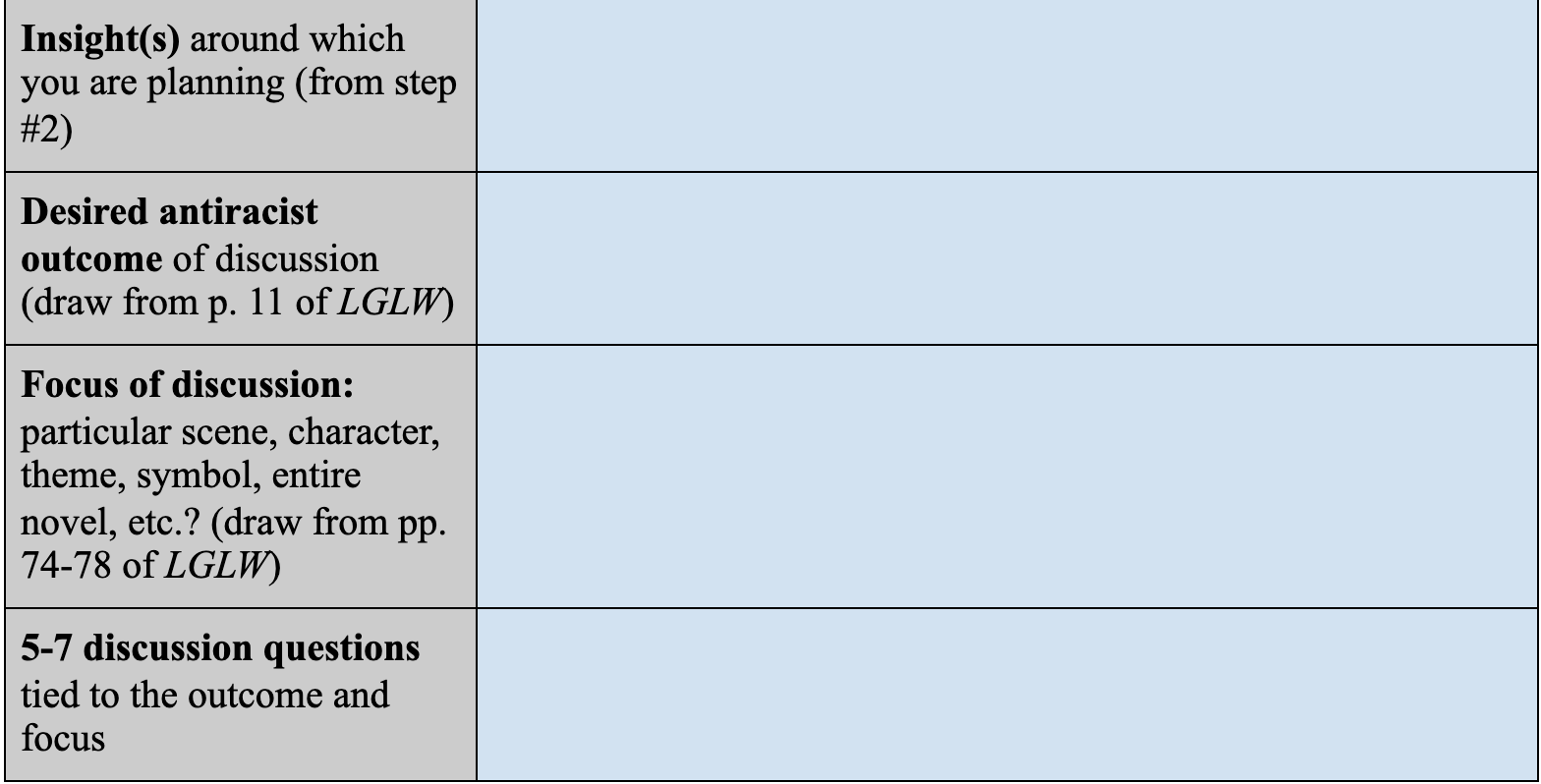

Critical Race Discussion Assignment

This is a multi-stage assignment I use in my Young Adult Lit + Anti-Racist Teaching undergraduate course. It unfolds over about 5 weeks and makes up the major action in one learning module, usually at the start of the semester. Most students in the course are studying to be high school or middle school English language arts teachers. Although at the center of this assignment is students facilitating a discussion, I should say that most of the learning happens in the steps leading up to the discussion and the steps after the discussion.

Assignment goals:

- Design and facilitate a critical race discussions about literature.

- Know and be able to use accurate critical race concepts while analyzing and discussing literature.

- Gain comfort/affective stamina analyzing and discussing anti-Blackness, racism, whiteness, etc. in literature.

Background:

This assignment leverages key ideas in Letting Go of Literary Whiteness by Carlin Borsheim-Black and Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides. Students have already read this book, and I anchor excerpts about white education discourse (p. 96-98) and critical race literary analysis (p. 74-78) to this assignment.

Texts:

These novels offer a variety of ways characters negotiate incidents of anti-Black racial violence and white supremacy. The characters also center or challenge whiteness in various, incomplete ways. These exact texts are not essential for the assignment, but a set that presents a variety of responses to racism, racialization, etc. is important.

- Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

- Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White by Lila Quintero Weaver

I have students facilitate their own discussions in pods as we read these novels over three weeks. Importantly, these discussion are open-ended without much direction from me. I have students audio record their discussions and, at the end of each week, transcribe a 5-10 minute portion of the discussion. Like the discussions, I don’t give much direction about what to transcribe, and they don’t know the exactly what we will do with this transcripts. This is important. “Choose a part of the conversation you think is important or interesting,” I say. At the start of each week before we move onto the next novel, I briefly ask them about what they transcribed and why, and what came to mind as they were transcribing. This brief touch keeps the transcriptions in view even though they are without much broader context at this point.

Part I: Pre Discussion Planning

After we’ve finished the novels and discussion, we revisit the key ideas in Letting Go of Literary Whiteness and turn toward the assignment.

Steps to Students:

- Annotate your 3 transcripts. Annotate them by looking for instances of white educational discourse (LGLW p. 96-98) and critical race literary analysis (LGLW p. 74-78). You might find some clear instances of these, wonder if these are happening in some places, or notice an absence of these. Make your annotations as comments in the margins of your transcriptions. Shoot for at least 10 annotations. Keep all this to yourself and don’t share among your podmates.

- Write insight statements. From the annotations you made, write 1 insight statement based upon each transcript. What’s an insight statement? An insight statement synthesizes smaller points (like your annotations) into one meaningful point so you can design learning around it. It’s a full sentence with subject, verbs, and perhaps conjunctions and other parts. Example: Pod sometimes agrees or supports white discussants to help them feel comfortable while discussing racism in the text, rather than pushing to deeper and less comfortable examination.

- Reflect on you own racial self (300 words). Reflect on your own racialized position and experiences that play into designing and leading a critical race discussion. In what ways do you feel competent or incompetent for this task? What emotions do you feel in your body (e.g., nervousness in your belly?). What specific prior experiences have influenced these feelings?

- Fill out the planning grid.

I then have 30 minute pre-discussion meetings with each student. In the meeting, we look at the alignment among the four parts of the planning grid, the quality of questions, the staging each question might need, and other aspects of inspiring dialogue. Most students are good to go after the meeting; some need to revise a bit and wait for me to approve their planning grid before leading the discussion. These meetings are time consuming but essential to the meaningfulness of the experience.

Part II: Students Lead Pod Discussions

Each students leads their pod in a 15-20 minute discussion based upon their planning grid. These discussions are not about their past discussions but rather about a character, scene, conflict, etc. from one of the novels. Depending on the length of class and size of pods (typically 4-6 people), there can be multiple pod discussion in the same period. Occasionally pods will run some of their discussions on their own outside of class. Be sure to audio record.

Part III: Post Discussion Analysis

- Reflect on you own racial self (300 words). Reflect on how your own racialized position played into leading the discussion. How did you feel while leading? What questions or parts of the discussion challenged you the most, and why? You should also consider how your own racialized position in context with that of your group played into your experience. (This applies even if you and everyone in your group identifies as white.)

- Annotate and analyze the discussion by (A) transcribing it and (B) annotating the transcript for evidence of your desired antiracist outcome (see your planning grid). Also continue looking for instances of white educational discourse (LGLW p. 96-98). Shoot for at least 10 annotations.

- Write insight statements. From the annotations you made, write 1-3 insight statements about the discussion – just like you did before.

- Draw conclusions (300 words). Write a conclusion that explains: How successful were you in achieving the antiracist outcome of your discussion, and why? What is your evidence for success, and/or what kind of evidence is missing?

I emphasize that having a “successful” discussion and meeting their antiracist goals is not necessary to be successful on this assignment. Without stating this point, students will be put in the position to manufacture a successful discussion.

Students turn in each of the 8 items listed above, in that order, in one document.

Coda

With so many parts and moving parts in this assignment, I also rolled this assignment out to students in an editable google doc. I gave them time to annotate the assignment sheet with questions in class, and then I answered the questions in that same document. This process helped surface layers that I hadn’t anticipated, and it made the whole thing seem more feasible to students.

Took a minute, but I got the sonic composition site back up. This work was equally fun and challenging. I’m glad my students took the risk.

Reading my students’ final self-evaluations and it’s still true: they need one another more than they need us. They need us too, of course. But supportive, healthy relationships with one another in class will make what they learn with us persist past the semester. Also true: we can set routines and forms that help facilitate these relationships among them. That’s actually one of the ways they need us.

I gave in this year. Instead of asking students to read an assignment sheet before class, I started rolling it out as an editable google doc in class. I have them read and annotate it together with comments in the margins. I then respond to their comments in the doc real time, and we talk through issues I hadn’t anticipated. Sometimes I’ll leave blanks in the sheet and ask “what do you think should go here?” Or, “I went back and forth about this part, what do you think?” The comments and my responses then stay in the margins of the assignment sheet for when students are later working on the assignment, or – even better – for students who couldn’t be there in class that day. It’s messy, but what I ask students to do is usually messay anyway. The practice has me thinking about other ways to unfix assignments and assignment sheets, letting students speak into what I’m asking them to do.

I rolled out a heavy assignment sheet to my class yesterday. It’s 2.5 single spaces pages because, welll, this professor likes things done in a certain way. But I had students annotate the assignment sheet in class with commenting priviledges. Then I responded real time in writing to thier questions. I’m thinking about how to make assignments sheets themselves peripheral objects of study – to kind of destabilize them– even as students go about doing what is on them.

I usually give a pre-class survey for students to fill out sometime before our first class session. It lets me know a bit about what I’m walking into and what adjustments/supports might be necessary. Here are some of the sentence starters/questions I am using this semester.

*For this class, one thing I’m excited about is…

*For this class, one thing I’m worried about is…

*In order for me to be successful in this class this semester, I will need…

*Some questions I have right now are….

*Is there anything else you need to share with me to start off the year?

Young adult lit + anti-racist teaching course

The floorplan is coming together for my young adult lit + anti-racist teaching course. Here is where we stand, with some last minute tweaks likely to happen before Monday.

Course focus:

This class focuses on reading and teaching young adult literature through anti-racist and anti-oppressive approaches. Since many contemporary applications of these approaches are made by current teachers, the course also connects your learning to the efforts current teacher activists are taking toward more liberating classrooms and curricula. Reading demand: high! Writing demand: low!

Learning objectives:

- Know and be able to use accurate critical race concepts while analyzing and discussing literature

- Design and facilitate critical race discussions about literature

- Gain comfort/affective stamina analyzing and discussing anti-Blackness, racism, whiteness, etc. in literature

- Analyze characteristics of young adult literature and reimagine what counts in the genre

- Evaluate young adult literature as an effective and creative tool capturing contemporary moments/realities

- Connect with English teachers who are teaching and developing anti-oppressive curriculum around young adult literature

Teaching Post-Election

I asked students two weeks ago how they wanted class tonight to feel, how they might want class to go. I’m not inclined to cancel class the day after an election, no matter how bad it goes. But I feel the need to gather insights from students and consider those when planning class – especially when those students aspire to be teachers. It’s my design inclination, I think. They wanted two things, one serious and one silly: A chance to process the election together and Tik Tok videos that might cheer them up.

To process, I turned to a favorite analog tool: feeling cards. I spread these out digitally on our Mural with this prompt: “Look through all the feeling cards and pick one that describes how you are feeling about the election. Pick more than one if need. But don’t pick too many.” We then did a 10 minute solo write around this prompt: Which cards did you choose and why? I asked them to write in prose, not in bullet points or outline form. I told students they would be invited to share what they write but would not be requited.

Then we wrote. Myself included.+

I reminded students of a norm we set together at the start of the semester: Use disagreements as an opportunity to learn, respect, and educate. I told them we set the norm before we might need it. We might need it tonight; who knows. So let’s speak it in the space and hold ourselves to it, if we can.

I then invited students to share what they wrote. I was clear to say, “What you wrote is for yourself. You are invited to share, but you are not required.” For students who shared, I asked them to read exactly what they wrote rather than paraphrase it. This was to give them a useful constraint, a script — so to speak. But they were also free to finish any thoughts the time limit had cut off or to comment on what they wrote if they felt it was necessary. I did this because feeling confined to what you wrote in a timed, inauthentic writing setting can be stifling. Sometimes you write what you mean. Other times you don’t and need to explain.

I gave students three filters — sentence starters, if you will — through which to listen and respond to one another, if they wanted. I offered these to direct the conversation and anticipate different positions students might hold in class. I felt these filters might promote generative interaction and give students productive ways to respond to one another. Here they are:

“I also feel that way because…”

“I hadn’t thought about…”

“Your response challenges me to…”

Some read. Some respond. Some listened. And everything spoken is sacred to the space, so I won’t share it here.

I then moved us to think about self and community care. I did this with four areas and asked students to drop one sticky note in each.

“One thing I can do right now to take care of myself is…”

“One thing we can do right now to take care of each other is…”

“One thing I can do in the coming weeks to take care of myself is…”

“One thing we can do in the coming weeks to take care of each other is…”

I feel the individual and collective is important. I feel the immediate and long-term is important.

Before we finished, I told students I wanted to return to what we did tonight at some point and talk with them as educators about it. I want to explain the reasons behind the order of things, the phrasing of things, and the design of things. At their request, one reason we did this is so they — as aspiring educators — could see and feel one way to help students process “day after” events. From the experiential standpoint, those purposes might not be clear, so we need to return and debrief later.

+What I wrote:

I picked the word “peaceful” because, to my credit, I feel like the boundaries I set for myself in the last 24 hours have been right on. I haven’t been glued to media, watching every single uptick in percentage points. I haven’t been doing electoral math in my head. And I haven’t let countless tweets or posts get their hooks in me. I’ve jumped over to a news site only a few times to get an update and jumped out before it could pull me in. I’m proud of this clarity and the boundary I set. I haven’t always known how to do that.

I also picked the word “tense” because I think it describes the relational state of some people in my family who have different social convictions and beliefs. I imagine us in this distant orbit with gravities pulling upon one another from afar as all these votes are counted, and I wonder what will happen to the orbits when it’s all finalized, whenever that may be. Orbits are pretty predictable unless space objects like meteors or NASA junk get in the way. [Metaphor incomplete.]

Me (Aug 2020): No late work will be accepted.

Me (Sept till infinity): Hey turn it in whenever you can. Whatever works for you. No worries. It’s all good. Glad you’re here. Hope you’re okay. Let me know if you need any help.

Teaching Through Non-Indictment

The non-indictment of Breonna Taylor’s killers came out a few hours before my evening class was to start. (Note: Brett Hankison was indicted for wanton endangerment unrelated to her death.) This isn’t the first time I’ve taught through a moment of racial violence. I know it won’t be the last. The impulse to address the moment is important, and there usually aren’t easy steps. So I’m sharing mine. Here’s are the pivots I made tonight. As always, I’m open to feedback, for I know I don’t have it all right.

I started class by acknowledged the moment we are in and the most urgent facts that students might or might not know. Breonna Taylor was killed 6 months ago in a botched police raid. Just announced in Louisville, no officers would be indicted for her murder. The “wanton endangerment” indictment is unrelated to murder. I emphasized that, for those of us following this story, we carry this stress and trauma in our bodies to class tonight. The ways we live through this stress depends on our own racial proximity to and experience of racial violence. It’s typically less if you are white. It’s more if you’re Black.

I also called the name of Aiyana Stanley-Jones, who was killed in a botched police raid in 2010 on the eastside of Detroit — for which there was no kind of justice. I said her name and explained this event so students would know that this particular kind of anti-Black, state-sanctioned violence (the botched raid) is a pattern — even here in Michigan. I told students how even today, organizers in Detroit say her name, paint her in murals, and carry her tiny legacy forward. She is known and remembered. Students needed to know this.

I told white students that no matter how badly they felt, their feelings would subside before folks of color. I told them that this applies to me as well since I am white. I told them they should think about their actions and the grace they should give the folks of color around them. I wish I would have given them specific examples of such actions I’ve taken and should have taken in the past. I told them that it’s not just their peers. It’s their professors too — especially Black women professors they may have. They are reliving trauma and fears. I told students they needed to know this.

I told students that the constant news cycle can be overwhelming and unhealthy. It can make the entire problem seem beyond their control. I suggested they think about what is in their locus of control. And one thing that is (aside from voting!) is recommitting yourself to studying to understand the roots and shapeshifting nature of white supremacy and racial violence. I said it’s not enough to know that something is wrong. You need to know how and why. You know when you’re sick. You to go the doctor to understand why so it can be fixed. Understand the nature of the problem so you can be of service where you are. I had planned to tell them to read Kimberlé Crenshaw’s original article on intersectionality. (Dig into the classics!) To read Angela Y. Davis’s book Are Prisons Obsolete? if they were just now hearing about this idea of abolition. To read Brittney Cooper’s Eloquent Rage. I wanted to give them specific things to read even though it’s outside of the course focus. I didn’t though. I don’t know why. So I need to follow up. It’s not enough to tell them to study without giving specific steps.

I told them that I fear it may be superficial, but as the organizer and leader of the class, I’m making the decision that the time we spend together in class tonight will be to honor the life of Breonna Taylor. What I didn’t tell them is that this idea comes from the Eucharist — that in some Anglican parishes, the rector may dedicate the Eucharist to someone who died recently. This is where the idea came from and why – at least in my private thoughts – it’s not an empty gesture. I told them the time we spend together and the focus you offer toward your education in this class period will be to honor her life. I told them people miss her profoundly right now. They miss what she sounded like. They miss what her neck smelled like because they hugged her in the kind of way that your face is in the other person’s neck. They miss all these things about her. We don’t and we can’t. But we’ll speak her name and offer our time to her life – as superficial as it may sound.

I then gave students a 5 minute break. Because somebody has to set up the zoom breakout rooms.