Emery Marc Petchauer

Theories of Change in Racial Consciousness: A Thought Exercise

This is a thought exercise I developed through the Race, Pedagogy, & Lit workshop series at Michigan State University.* The exercise tries to create dialogue and understanding among colleagues who might hold similar commitments to antiracism but take very different steps toward antiracist outcomes in courses and around campus. In a charitable environment, such colleagues are eager to understand one another. In an uncharitable environment, such colleagues may be suspicious of one another. The exercise is geared toward either environment.

Ground zero is this question:

This question draws from Eve Tuck’s article “Suspending Damage,” which discusses theories of change in social science research. The social science context isn’t important. Rather, it’s important people think about the tacit theories of change they have adopted regarding how people like themselves grow in racial consciousness.

The framing of this question toward people “like you” is useful. First, it allows people to take up the question in a range of ways. Second, it allows facilitators to prompt in certain directions, like asking white folks to think about how other white folks grow in racial consciousness.

We then link this question with two others relevant to the campus context. These three questions and the possible answers make up the thought matrix of the exercise. How you answer these questions reveals key components about the overall theory of change that guides your actions.

We then think about the kinds of actions that would follow from different configurations of answers. You can see one configuration in the series of green answers below. This person would likely be very vocal, all the time, and everywhere. Do you know anyone like this? Is this you? This person would also likely design courses and campus programing for explicit antiracist outcomes. The point here isn’t to evaluate this theory of change but to understand the actions that would follow from this particular configuration of answers.

But then if you were to change just one answer, the ensuing actions would also change. In this case below, the red answer would shape the curricular and campus programming decision faculty and staff make. This person would not wrap all courses and programming around antiracist outcomes, even though the answers in the first two columns have not changed.

And there are other options too. In the configuration below, this person feels less responsible for initiating growth in others. This might mean they are less vocal about issues that do not directly impact them.

And so on. Once again, the point in this exercise is not to evaluate theories of change. Some of them might be right. Some of them might be wrong. And there are always contradictions among theories of change because they operate across many scales and temporalities (another point from Tuck). Similarly, the point is not to reach consensus about which set of answers is right (though that may be an important step in a different process). The point is to understand how different answers to key question will result in different actions. Colleagues may be very similar to one another with respect to how they answer these questions, but the actions that result may be very different. Or colleagues may be very different from one another with respect to how they answer these questions, and that is why their actions are different.

I imagine there are many ways to remix this exercise. Different sets of questions and answers could populate this matrix and shift the purpose of the activity. The phrase “racial consciousness” early on could be substituted with something else as well.

*Thanks to my collaborators Briona S. Jones and Sen Kim for co-facilitating this Race, Pedagogy, and Lit series.

Critical Race Discussion Assignment

This is a multi-stage assignment I use in my Young Adult Lit + Anti-Racist Teaching undergraduate course. It unfolds over about 5 weeks and makes up the major action in one learning module, usually at the start of the semester. Most students in the course are studying to be high school or middle school English language arts teachers. Although at the center of this assignment is students facilitating a discussion, I should say that most of the learning happens in the steps leading up to the discussion and the steps after the discussion.

Assignment goals:

- Design and facilitate a critical race discussions about literature.

- Know and be able to use accurate critical race concepts while analyzing and discussing literature.

- Gain comfort/affective stamina analyzing and discussing anti-Blackness, racism, whiteness, etc. in literature.

Background:

This assignment leverages key ideas in Letting Go of Literary Whiteness by Carlin Borsheim-Black and Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides. Students have already read this book, and I anchor excerpts about white education discourse (p. 96-98) and critical race literary analysis (p. 74-78) to this assignment.

Texts:

These novels offer a variety of ways characters negotiate incidents of anti-Black racial violence and white supremacy. The characters also center or challenge whiteness in various, incomplete ways. These exact texts are not essential for the assignment, but a set that presents a variety of responses to racism, racialization, etc. is important.

- Ghost Boys by Jewell Parker Rhodes

- All American Boys by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely

- Darkroom: A Memoir in Black and White by Lila Quintero Weaver

I have students facilitate their own discussions in pods as we read these novels over three weeks. Importantly, these discussion are open-ended without much direction from me. I have students audio record their discussions and, at the end of each week, transcribe a 5-10 minute portion of the discussion. Like the discussions, I don’t give much direction about what to transcribe, and they don’t know the exactly what we will do with this transcripts. This is important. “Choose a part of the conversation you think is important or interesting,” I say. At the start of each week before we move onto the next novel, I briefly ask them about what they transcribed and why, and what came to mind as they were transcribing. This brief touch keeps the transcriptions in view even though they are without much broader context at this point.

Part I: Pre Discussion Planning

After we’ve finished the novels and discussion, we revisit the key ideas in Letting Go of Literary Whiteness and turn toward the assignment.

Steps to Students:

- Annotate your 3 transcripts. Annotate them by looking for instances of white educational discourse (LGLW p. 96-98) and critical race literary analysis (LGLW p. 74-78). You might find some clear instances of these, wonder if these are happening in some places, or notice an absence of these. Make your annotations as comments in the margins of your transcriptions. Shoot for at least 10 annotations. Keep all this to yourself and don’t share among your podmates.

- Write insight statements. From the annotations you made, write 1 insight statement based upon each transcript. What’s an insight statement? An insight statement synthesizes smaller points (like your annotations) into one meaningful point so you can design learning around it. It’s a full sentence with subject, verbs, and perhaps conjunctions and other parts. Example: Pod sometimes agrees or supports white discussants to help them feel comfortable while discussing racism in the text, rather than pushing to deeper and less comfortable examination.

- Reflect on you own racial self (300 words). Reflect on your own racialized position and experiences that play into designing and leading a critical race discussion. In what ways do you feel competent or incompetent for this task? What emotions do you feel in your body (e.g., nervousness in your belly?). What specific prior experiences have influenced these feelings?

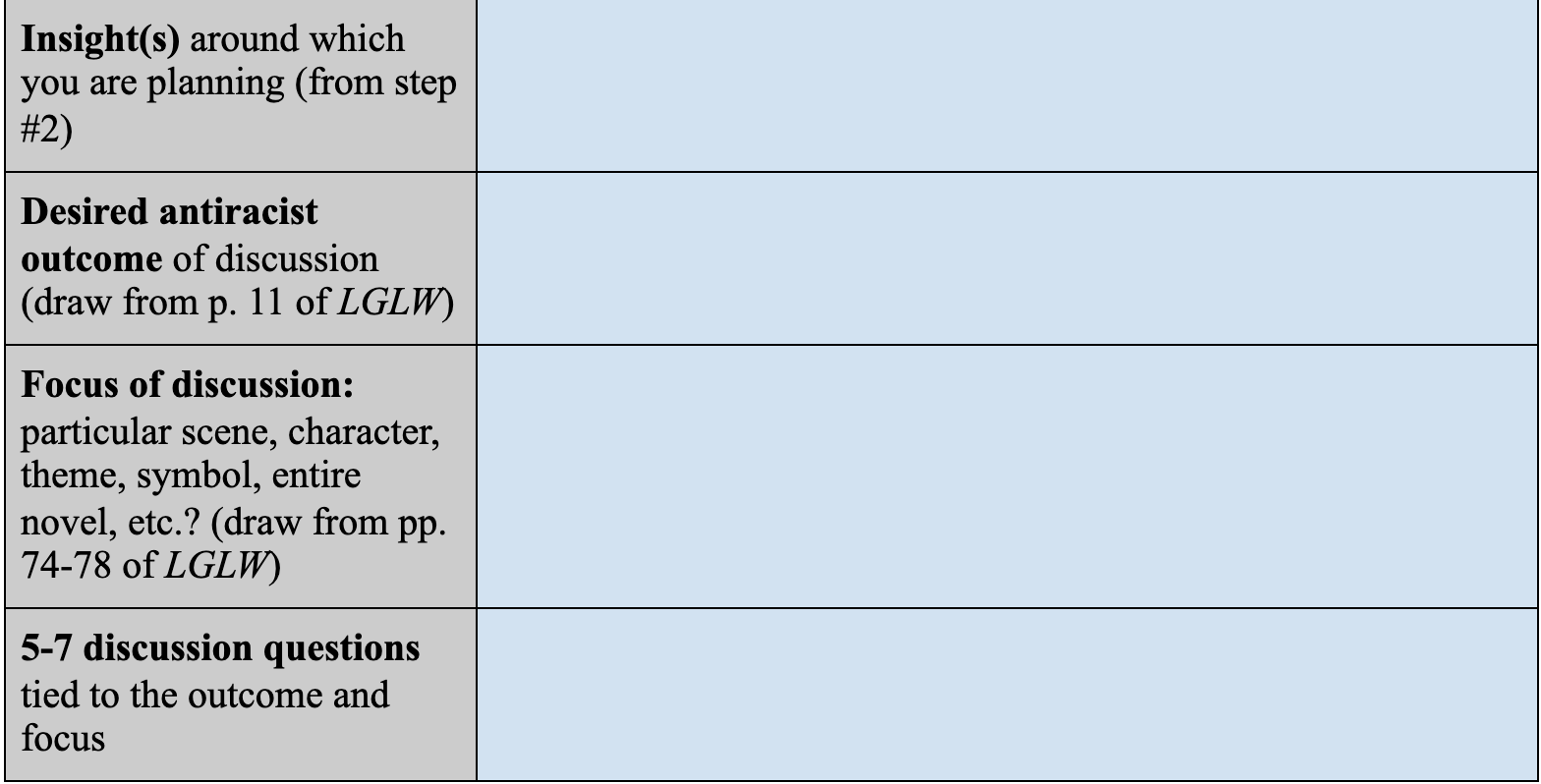

- Fill out the planning grid.

I then have 30 minute pre-discussion meetings with each student. In the meeting, we look at the alignment among the four parts of the planning grid, the quality of questions, the staging each question might need, and other aspects of inspiring dialogue. Most students are good to go after the meeting; some need to revise a bit and wait for me to approve their planning grid before leading the discussion. These meetings are time consuming but essential to the meaningfulness of the experience.

Part II: Students Lead Pod Discussions

Each students leads their pod in a 15-20 minute discussion based upon their planning grid. These discussions are not about their past discussions but rather about a character, scene, conflict, etc. from one of the novels. Depending on the length of class and size of pods (typically 4-6 people), there can be multiple pod discussion in the same period. Occasionally pods will run some of their discussions on their own outside of class. Be sure to audio record.

Part III: Post Discussion Analysis

- Reflect on you own racial self (300 words). Reflect on how your own racialized position played into leading the discussion. How did you feel while leading? What questions or parts of the discussion challenged you the most, and why? You should also consider how your own racialized position in context with that of your group played into your experience. (This applies even if you and everyone in your group identifies as white.)

- Annotate and analyze the discussion by (A) transcribing it and (B) annotating the transcript for evidence of your desired antiracist outcome (see your planning grid). Also continue looking for instances of white educational discourse (LGLW p. 96-98). Shoot for at least 10 annotations.

- Write insight statements. From the annotations you made, write 1-3 insight statements about the discussion – just like you did before.

- Draw conclusions (300 words). Write a conclusion that explains: How successful were you in achieving the antiracist outcome of your discussion, and why? What is your evidence for success, and/or what kind of evidence is missing?

I emphasize that having a “successful” discussion and meeting their antiracist goals is not necessary to be successful on this assignment. Without stating this point, students will be put in the position to manufacture a successful discussion.

Students turn in each of the 8 items listed above, in that order, in one document.

Coda

With so many parts and moving parts in this assignment, I also rolled this assignment out to students in an editable google doc. I gave them time to annotate the assignment sheet with questions in class, and then I answered the questions in that same document. This process helped surface layers that I hadn’t anticipated, and it made the whole thing seem more feasible to students.